|

|

Kota Kuala Selangor

The Twin Guardians of Selangor

Located near the mouth of the

Selangor River, the fort complex at Kuala Selangor

actually consists of two forts – the larger stone fort of Kota Malawati

on

Bukit Selangor and a smaller earthworks fort on Bukit Tanjong Keramat

about

a kilometre and a half to the northeast. Protected by steep hill

slopes,

flanked on three sides by a sharp bend of the Selangor River and

surrounded

on all sides by thick mangrove swamps, it was an ideal defensive

position

for a fort. Its position on the mouth of the Selangor river, with a

panoramic

view of the Straits of Melaka and the Klang Valley, also gave the fort

vital

strategic importance. Located near the mouth of the

Selangor River, the fort complex at Kuala Selangor

actually consists of two forts – the larger stone fort of Kota Malawati

on

Bukit Selangor and a smaller earthworks fort on Bukit Tanjong Keramat

about

a kilometre and a half to the northeast. Protected by steep hill

slopes,

flanked on three sides by a sharp bend of the Selangor River and

surrounded

on all sides by thick mangrove swamps, it was an ideal defensive

position

for a fort. Its position on the mouth of the Selangor river, with a

panoramic

view of the Straits of Melaka and the Klang Valley, also gave the fort

vital

strategic importance.

The fort was first constructed some time in the early 16th

century by Tun

Mahmud, a son of Sultan Mahmud, the last Sultan of Melaka, from which

he

administered the state on behalf of the Johor empire . The Bugis

established

themselves in Selangor in the 17th century and installed Raja Lumu as

Selangor’s

first Sultan in 1756. Raja Lumu, who took the title Sultan Salehudin

Shah,

established himself at the Kota Malawati, replacing its earlier

earthworks

with stout stone walls and ringing its perimeter with cannon. The fort was first constructed some time in the early 16th

century by Tun

Mahmud, a son of Sultan Mahmud, the last Sultan of Melaka, from which

he

administered the state on behalf of the Johor empire . The Bugis

established

themselves in Selangor in the 17th century and installed Raja Lumu as

Selangor’s

first Sultan in 1756. Raja Lumu, who took the title Sultan Salehudin

Shah,

established himself at the Kota Malawati, replacing its earlier

earthworks

with stout stone walls and ringing its perimeter with cannon.

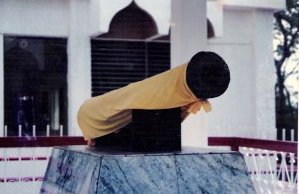

Sultan Ibrahim Shah who succeeded him further improved the

fort’s defences

with the construction of additional walls at the base of the hill and

the

placement of even more cannon, including a huge cannon with the

name

of Seri Rambai. A gift from the Sultan of Acheh, this cannon

was originally

given by the Dutch to Sultan Riayat Shah Shah III of Johor but was

captured

by the Achinese when they sacked his capital in 1613. According to

Dutch

records, the fort was at the time was equipped with a total of 68

cannon.

It was also at this time that the second earthworks fort was built at

Bukit

Tanjong Keramat, to help support the main fort from any surprise

flanking

attacks by sea. Sultan Ibrahim Shah who succeeded him further improved the

fort’s defences

with the construction of additional walls at the base of the hill and

the

placement of even more cannon, including a huge cannon with the

name

of Seri Rambai. A gift from the Sultan of Acheh, this cannon

was originally

given by the Dutch to Sultan Riayat Shah Shah III of Johor but was

captured

by the Achinese when they sacked his capital in 1613. According to

Dutch

records, the fort was at the time was equipped with a total of 68

cannon.

It was also at this time that the second earthworks fort was built at

Bukit

Tanjong Keramat, to help support the main fort from any surprise

flanking

attacks by sea.

Because Selangor allied itself with the Achinese when they

attacked Dutch

Melaka in 1784, a fleet of 11 Dutch ships led by Dirk van Hogen and

several

vessels belonging to their ally, Raja Muhammad Ali of Siak, sailed to

Kuala

Selangor in July that year and shelled the fort mercilessly for two

weeks.

On August 2, a combined force of Dutch troops and Siak Malays landed

and

stormed the hill, driving Sultan Ibrahim’s forces into the surrounding

jungle.

The Dutch occupied the fort, renaming Kota Malawati ‘Altingburg’ and

calling

Kota Tanjong Keramat ‘Utrecht’. Because Selangor allied itself with the Achinese when they

attacked Dutch

Melaka in 1784, a fleet of 11 Dutch ships led by Dirk van Hogen and

several

vessels belonging to their ally, Raja Muhammad Ali of Siak, sailed to

Kuala

Selangor in July that year and shelled the fort mercilessly for two

weeks.

On August 2, a combined force of Dutch troops and Siak Malays landed

and

stormed the hill, driving Sultan Ibrahim’s forces into the surrounding

jungle.

The Dutch occupied the fort, renaming Kota Malawati ‘Altingburg’ and

calling

Kota Tanjong Keramat ‘Utrecht’.

The Dutch strengthened the fort with stouter walls and

larger cannon, and

built a lighthouse on the hill summit. However, their stay at

Altingburg

and Utrecht was to be short-lived. Less than a year later, on 28 June

1785,

Sultan Ibrahim’s forces, with the help of 2,000 Pahang Malays, launched

a

surprise night attack on the fort immediately after evening Isyak

prayers

and overwhelmed it completely. The Dutch garrison under Gerardu

Zwykhardt

and August Gravensteyu were driven back to the sea. Another Dutch fleet

was

dispatched shortly and succeeded in blockading the fort for over a

year.

However, the Dutch did not dare launch any land attacks on its stout

defences

and steep hills and the fort was to remain in Malay hands until British

gunboats

pounded it to submission in 1871. The Dutch strengthened the fort with stouter walls and

larger cannon, and

built a lighthouse on the hill summit. However, their stay at

Altingburg

and Utrecht was to be short-lived. Less than a year later, on 28 June

1785,

Sultan Ibrahim’s forces, with the help of 2,000 Pahang Malays, launched

a

surprise night attack on the fort immediately after evening Isyak

prayers

and overwhelmed it completely. The Dutch garrison under Gerardu

Zwykhardt

and August Gravensteyu were driven back to the sea. Another Dutch fleet

was

dispatched shortly and succeeded in blockading the fort for over a

year.

However, the Dutch did not dare launch any land attacks on its stout

defences

and steep hills and the fort was to remain in Malay hands until British

gunboats

pounded it to submission in 1871.

It is unsurprising that a fort so steeped in history would

also be the subject

of myth and legend. At the entrance to the main courtyard on the

summit

of the hill is a large rock tablet and it is said that a palace maiden

was

beheaded at the rock for allegedly having an affair with someone

outside

the palace. According to the legend, her blood poured all over rock and

nearby

areas to serve as a reminder to other women not to commit adultery.

Even

today, red sap runs from a nearby tree, often referred to as Pokok

Berdarah

(the Bleeding Tree), and many believe this to be the blood of the

beheaded

maiden. It is unsurprising that a fort so steeped in history would

also be the subject

of myth and legend. At the entrance to the main courtyard on the

summit

of the hill is a large rock tablet and it is said that a palace maiden

was

beheaded at the rock for allegedly having an affair with someone

outside

the palace. According to the legend, her blood poured all over rock and

nearby

areas to serve as a reminder to other women not to commit adultery.

Even

today, red sap runs from a nearby tree, often referred to as Pokok

Berdarah

(the Bleeding Tree), and many believe this to be the blood of the

beheaded

maiden.

However, English sources provide a different twist to the

tale. On the day

the British gunboat Rinaldo shelled the fort, the Malays saw that the

place

was no longer tenable. A Malay chief is said to have cut the

throat

of an innocent girl and scattered her blood over the guns that he was

forced

to abandon. Her body was left on a large slab of stone before the

main

gate of the fort, a slab which is still shown as "the Stone of

Sacrifice",

because the murder was understood at the time to represent the

blood-offering

of a human victim as a prayer for victory. Most probably the poor

girl

was killed in order that her vengeful spirit should haunt the guns of

the

fort and make them a curse and a danger to the men in whose hands they

were

to fall. However, English sources provide a different twist to the

tale. On the day

the British gunboat Rinaldo shelled the fort, the Malays saw that the

place

was no longer tenable. A Malay chief is said to have cut the

throat

of an innocent girl and scattered her blood over the guns that he was

forced

to abandon. Her body was left on a large slab of stone before the

main

gate of the fort, a slab which is still shown as "the Stone of

Sacrifice",

because the murder was understood at the time to represent the

blood-offering

of a human victim as a prayer for victory. Most probably the poor

girl

was killed in order that her vengeful spirit should haunt the guns of

the

fort and make them a curse and a danger to the men in whose hands they

were

to fall.

On the narrow stone path leading to the entrance of the

fort is also located

a Poisoned Well which was used to execute traitors. It was filled with

a

poisonous mixture of latex and juice from bamboo shoots and victims

were

lowered into the well to a slow and painful death. There are many

Malay

forts in the Peninsula that have such poisoned wells and it was

probably

a commonly-used form of capital punishment.. On the narrow stone path leading to the entrance of the

fort is also located

a Poisoned Well which was used to execute traitors. It was filled with

a

poisonous mixture of latex and juice from bamboo shoots and victims

were

lowered into the well to a slow and painful death. There are many

Malay

forts in the Peninsula that have such poisoned wells and it was

probably

a commonly-used form of capital punishment..

The origin of the name of Bukit Tanjung Keramat also

involves a maiden. It

is said that there was once lived a young local girl named Rabiah who

vanished

without a trace just before her wedding day. Rabiah had gone to a

nearby

pool, just below (Bukit Tanjung Keramat) to draw water but,

unfortunately,

that was the last anyone saw of her. Her family searched frantically

for

but all they found was her scarf, hanging from a branch. That night,

she

appeared to her parents in a dream, telling them that she had gone

somewhere

very peaceful and that there was no need to look for her. Rabiah’s

parents

then dedicated a shrine (‘keramat’) to her at the spot where the scarf

was

found and the hill had been known as Bukit Tanjung Keramat ever since.

To

this day, people visit the shrine asking for favours and bringing

offerings

such as chicken, flowers, fruit and incense. The origin of the name of Bukit Tanjung Keramat also

involves a maiden. It

is said that there was once lived a young local girl named Rabiah who

vanished

without a trace just before her wedding day. Rabiah had gone to a

nearby

pool, just below (Bukit Tanjung Keramat) to draw water but,

unfortunately,

that was the last anyone saw of her. Her family searched frantically

for

but all they found was her scarf, hanging from a branch. That night,

she

appeared to her parents in a dream, telling them that she had gone

somewhere

very peaceful and that there was no need to look for her. Rabiah’s

parents

then dedicated a shrine (‘keramat’) to her at the spot where the scarf

was

found and the hill had been known as Bukit Tanjung Keramat ever since.

To

this day, people visit the shrine asking for favours and bringing

offerings

such as chicken, flowers, fruit and incense.

References:

- “Kota-Kota Melayu”, Abdul Halim Nasir, 1990, Dewan

Bahasa

dan Pustaka

- “Sejarah dan Kesan-Kesan Sejarah Kuala Selangor”,

Yusoff

Hasan P.J.K.. 1981, Penerbitan Tra-Tra

- "A History of the Peninsular Malays with Chapters on

Perak

& Selangor" R.J. Wilkinson, C.M.G (Pub Kelly & Walsh Ltd.)

- "Papers on Malay Subjects" Edited by R.J. Wilkinson

(Oxford

University Press)

Write to the author: sabrizain@malaya.org.uk

The

Sejarah Melayu

website is

maintained solely by myself and does not receive any funding

support from any governmental, academic, corporate or other

organizations. If you have found the Sejarah Melayu website useful, any

financial contribution you can make, no matter how small, will be

deeply appreciated and assist greatly in the continued maintenance of

this site.

|

|