|

|

The Battle for Klang

With the death of Sultan Ibrahim

in 1826, Selangor fell on evil days - Sultan Muhammad, the next ruler,

was unable to control his chiefs. Between intervals of comparative

quiet, said Swettenham, in his book 'British Malaya', the "normal state

of Selangor was robbery, battle and murder". When Sultan Muhammad died

in 1857, there was a disputed succession, and Abdul Samad, who

eventually became Sultan, had all but given up the struggle to maintain

order. With the death of Sultan Ibrahim

in 1826, Selangor fell on evil days - Sultan Muhammad, the next ruler,

was unable to control his chiefs. Between intervals of comparative

quiet, said Swettenham, in his book 'British Malaya', the "normal state

of Selangor was robbery, battle and murder". When Sultan Muhammad died

in 1857, there was a disputed succession, and Abdul Samad, who

eventually became Sultan, had all but given up the struggle to maintain

order.

A key factor in the outbreak of the Selangor civil war was the feudal

system where the Sultan granted parts of the State, usually river

valleys, to kinsmen and nobles to be ruled by them. The key chiefdoms

were the valleys of the Selangor river, the Klang river, Lukut and

Bernam - the Sultan himself held the Langat river valley. The grant was

limited to the life of the holder and on their death, this frequently

resulted in their kinsmen or even other chiefs fighting over the

chiefdom. The landless nobleman was also often tempted to raise an

army, oust a weak rival and then negotiate with the Sultan for

recognition of his conquest.

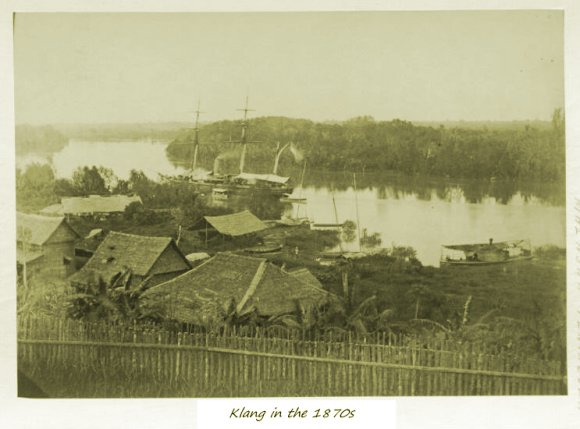

A key economic factor in the Selangor Civil War was the growth of the

tin mining industry. For several centuries, the wealth of Selangor had

lain in its exports of tin. However, output from these mines was low.

This all changed when, in 1857 Raja Abdullah bin Raja Jaafar, the

ruling chief at Klang, introduced Chinese miners into what was to

become the Kuala Lumpur tin-field. By 1871 there were 12,000 Chinese in

Selangor. The recruitment of Chinese tin-miners by many of the Malay

chiefs had brought new and more efficient techniques, a large labour

force and vastly increased production . The now vastly increased

revenues of the tin trade became a bone of contention between the Malay

chiefs and the various clans of Chinese miners also quarrelled over

control of the tin-fields.

<>

<> Sultan Abdul Samad

(seated on the chair in the centre) and his retinue.

<> Another factor that led to the outbreak of the Civil War was

the discontent that had been simmering over decades between the Bugis

rulers of Selangor and the Malays of Sumatran descent, such as the

orang Rawa, Mandailing and Minangkabau, whose ancestors had bitterly

fought the Bugis during the long wars of the 18th century. Raja

Abdullah, like the Sultan and the other chiefs, was a Bugis and his men

occupied the coast and most of the estuary as far as his headquarters

at Klang. Beyond this point the river was controlled by Sumatran Malays

under their headman the Dato Dagang. The Sumatran Malays made a living

as merchants in the interior or by transporting goods up and down the

river and they bitterly resented the import and export duties levied on

them by their Bugis rulers.

This discontent had been made worse when the Sultan canceled a

betrothal of marriage between his only daughter, 'Arfah, with Raja

Mahadi and instead married her off to the younger brother of the Sultan

of Kedah, Tunku Zia'u'd-din, usually known as Tunku Kudin (seated left

in the picture). The Sultan also made Tunku Kudin his Viceroy and Tunku

Kudin had with him a force of 500 Kedah Malays and an army of Bugis,

Arab and European mercenaries to impose his will. The presence of this

Kedah interloper and his army of 'foreigners' caused great resentment

among many of the Selangor chiefs.

In 1866, fighting broke out between the armies of Raja Abdullah and

Raja Mahadi for control of Klang, beginning almost ten years of

warfare. It started with a quarrel between a Bugis and a Sumatran

Malay, which resulted in the Sumatran being murdered. As was the

custom, the Dato' Dagang demanded blood money as compensation from Raja

Abdullah. Raja Abdullah did nothing to settle the grievance and the

Dato' Dagang appealed to Raja Mahadi for assistance. Raja Mahadi used

this a pretence to attack Klang with 200 of his men, using junks that

converged on the town from both directions, upstream and

downstream.Raja Mahadi occupied the fort on the hill overlooking Klang

and Raja 'Abdullah fled to Malacca as soon the fighting began, leaving

his son Isma'il to continue the battle. Some time later, Raja Abdullah

returned and attempted to re-take Klang, having borrowed enough money

from Chinese merchants to èquip an expedition. He had fitted out

two ships as war vessels, with cannon and sailed up the river, taking

position just below the fort.

Raja Abdullah's attack on Raja Mahdi failed miserably as he

was unable to elevate the guns in his war boats sufficiently high

enough to bombard Raja Mahadi's fort and the shots fell short, either

landing in the river or on the river bank. Raja Abdullah withdrew his

forces and left with his relatives and followers for Malacca, and

subsequently, Singapore. The fighting had lasted for about five months

and Raja Mahadi had attained his ambition of making himself the ruler

of Klang. But the matter was by no means closed.

Raja Abdullah's son, Raja Ismail, gathered another force to re-take

Klang, consisting of about 100 Ilanuns from Riau, kinsmen from Lukut

and Bugis mercenaries. In August, 1869, he reached the estuary of the

Klang River under cover of darkness and attacked the first of Raja

Mahdi's forts at Kuala Klang. The attack was a complete surprise -

though the fort was occupied by 30 of Raja Mahdi's men, none of its

guns were manned and no one was on watch. Some of the defenders were

killed but most fled back to Klang, bringing news of the defeat.

Ismail's force suffered one casualty - a man slashed by his own brother

who mistook him for an enemy as he wriggled through a gun embrasure to

get inside the fort.

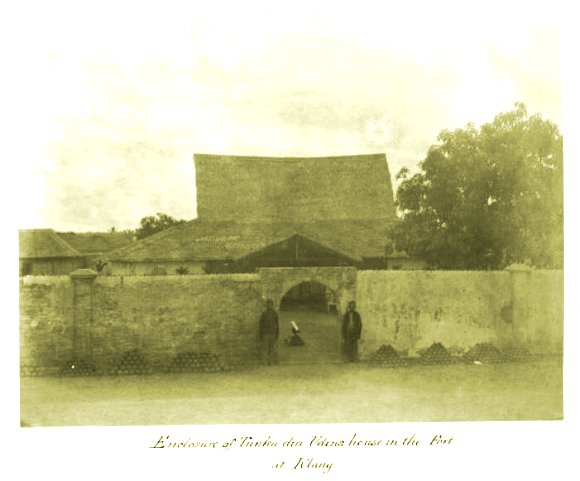

Raja Ismail then proceeded to Klang. However, he only had 100 men,

which was not sufficient to overpower Raja Mahadi's fort in Klang and

he appealed to Tunku Kudin for assistance. Tunku Kudin and 500 Kedah

Malays joined the attack. The two forces now settled down for a long

siege, with Raja Mahdi's forces entrenched in the fort on the hill and

Tunku Kudin's forces camped in the fortified stockade that had been

build around Gedung Raja Abdullah just half a kilometre below. Both

sides dug in their fortified defences, content only to bombard each

other's positions with their cannon or use their muskets to snipe at

exposed enemy soldiers. Tunku Kudin only occasionally launched sorties

against the fort's ramparts, using his Bugis mercenaries - more to

harry and worry its defenders than to overwhelm them.

Tunku Kudin was a determined, single-minded man with a deep

perseverance that

none of his rivals possessed - rather than risk a failed frontal

assault, his army just sat down before Raja Mahadi's fort, blockading

the river so efficiently that neither food nor tin entered the town. He

did not attempt to carry it by assault but simply threatened it and

worried it for eighteen weary months, starving it of supplies and

ruining its trade with the interior. The theatrical valour of Raja

Mahadi was no match for Tunku Kudin's persistence - Raja Mahadi's

storehouses lay empty, his money ran out and his followers began

deserting him. In March 1870, Raja Mahdi was forced to abandon Klang

and retreated to Kuala Selangor.

At Kuala Selangor, we now meet another towering figure in the Selangor

Civil War - Syed Mashhor bin Syed Muhammad Ash-Sahab, known as Che Soho

to his Chinese allies. Syed Mashhor (centre in long head dress) was

from Pontianak in Borneo, a Malay of Arab descent and already known as

a fearless fighter. Early in 1870, he had been sent by Tunku Kudin to

take charge of the fort at Kuala Selangor. However, shortly after he

arrived, he recieved news that his brother had been killed at Langat by

Raja Yaakob - a son of the Sultan and Tunku Kudin's brother-in-law. He

vowed vengeance and from that moment on became a sworn enemy of the

Sultan and his Viceroy Tunku Kudin, abandoning the fort to Raja Mahadi

and joining with him in his war against Tunku Kudin in the years to

come.

For more images, see www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.10154808032077988

Write to the author: sabrizain@malaya.org.uk

The

Sejarah Melayu

website is

maintained solely by myself and does not receive any funding

support from any governmental, academic, corporate or other

organizations. If you have found the Sejarah Melayu website useful, any

financial contribution you can make, no matter how small, will be

deeply appreciated and assist greatly in the continued maintenance of

this site.

|

|